Approx. reading time:

There’s nothing I like better than a good turn of phrase. I adore the cleverness behind well-constructed writing, the sort that sings along to a melody playing only in the author’s mind, each word so meticulously chosen for tonality and nuance that the music is heard by the reader, as well. I try my best to deliver it in my own work. It is with this love for the craft that, in my pitch for this retrospective, I wrote the following words about Wes Anderson:

I am a vocal hater of Wes Anderson. I hate how his films are 90% aesthetic, and in a way that brings no value to the storytelling. I don’t give a shit about his palette, his obsessive need for symmetry, or his fondness for making characters quirky to the point of caricature. I question the adoration for his films; he is nothing more than a basic bitch in twee wrapping.

I concede, however, that my opinion is shaped by the fact that I’d watched only one of his films in its entirety. I’d tried to watch two more, but tuned out less than 20 minutes into each because I couldn’t get past the Anderson-ness of it all. I skipped all the others, having gagged at the homogeneity in their trailers. My opinion is admittedly unfair.

And so, with Anderson’s Asteroid City set for wide release soon, I figured it was time to address this hostile prejudice. I asked my editor if she’d be interested in a piece where I would watch all ten of his films to date in an attempt to finally “get” it—whatever “it” might be.

I believe I had her at “basic bitch in twee wrapping.”

Without any heart driving these images, however, we get the equivalent of a cinematic jelly baby: a brightly colored, deliciously shaped confection that disappoints with its relative blandness.

Could this descent into the mind of a director I hated change my mind? Would subjecting myself to 993 minutes of pure, unadulterated Wes Anderson get me to like him? Is this long-winded intro, stuffed with moments of patting myself on the back for my own cleverness, an attempt at parodying the filmmaker’s penchant for doing the same?

Only one of those questions can be answered with a definitive “Yes”. As for the others, well… Keep reading, I suppose.

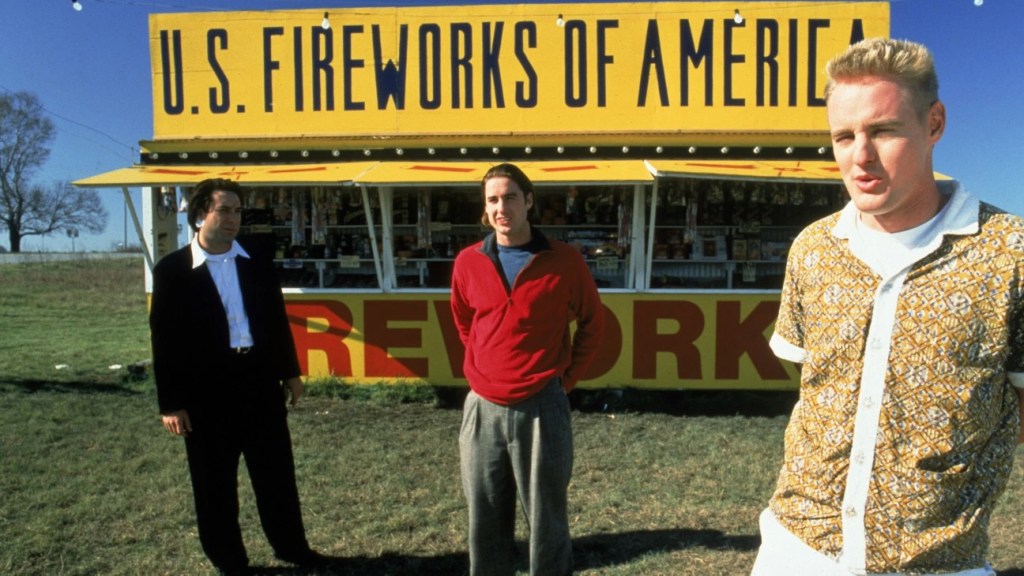

Our journey begins with Bottle Rocket (1996), a film whose most remarkable achievement was that it bagged Wes Anderson a second film deal. Not only were the characters bereft of any believable reason for sticking with each other, but they were also infuriatingly lacking in depth.

Dignan (Owen Wilson) is a crazy, free-wheeling conman who wants desperately to be a professional criminal. We’re unsure why. Anthony (Luke Wilson) is his best friend, who reluctantly joins him on his escapades. We’re unsure why. Rounding out the wannabe gang is Bob (Robert Musgrave), a wealthy, nebbish biscuit of a man looking to add meaning to his life by stealing money he doesn’t need.

His motivations are clear, at least.

After Anthony pesters (read: badgers) a Paraguayan hotel maid into falling in love with him, Dignan’s abandonment issues lead to a falling out. Months later, they reunite, reconcile because Dignan is just so lovable even though he’s addressed none of the issues that make him a bad friend, and then go on a heist featuring racist caricatures as additional members of their crew.

The film ends with Anthony and Bob visiting Dignan in prison, and all is forgiven because… Dignan is just so lovable even though he’s addressed none of the issues that make him a bad friend?

It wasn’t the best start to this whole Wes Anderson experiment, but it at least gave me a list of things to look out for:

- Underdeveloped characters

- Hollow interpersonal relationships

- Lack of personal accountability and growth

- Casual racism

If he could fix any of these issues in the next films, then I can say that he’s at least cleared the incredibly low bar he’d set for himself.

Rushmore (1998) was a marginal improvement. While Max Fischer (Jason Schwartzman) is a more fully fleshed-out protagonist, he is also an unlikeable one, seeing himself above most others and acting with a sense of entitlement that reflects this position. He only concedes to his faults because he has lost, not because he sees the need to be better. It’s indicative of a smugness that pervades some of Anderson’s later work.

Yet, with Rushmore insisting that we sympathize with Max, there’s also the undertone that the arrogant little shit we see onscreen is begging us to love him, warts and all, without doing any of the work to earn our love.

Now, I consider myself a bit of a romantic, and an unaddressed desire for unconditional love is something I’ve personally struggled with for much of my life. I get where Max—and by extension, Wes Anderson—is coming from. But it’s also an immature take on the need for acceptance, especially since Max commits borderline sociopathic acts without any real remorse. Empathy isn’t an excuse for permissiveness, which is what Rushmore unintentionally advocates.

Two films in, and it’s easy to see how fans could likely have gone on to see Tom from 500 Days of Summer as the good guy, too.

By the time I reached the third film, The Royal Tenenbaums (2001), I’d grown a little apprehensive. It was the only movie I’d been able to finish before, and I recalled enjoying it when I was 15. I was worried that rewatching it would mar a happy memory.

Thankfully, 15-year-old me was right: The Royal Tenenbaums is, in fact, a good movie, and showed for the first time Wes Anderson’s potential for making emotionally resonant films.

Themes of family, loneliness, longing, and forgiveness are strongly represented by the family members’ respective storylines, with Anderson’s trademark deadpan dialogue underscoring the emotional distance between each of them. It’s often the case that his characters are too distant to be relatable, but in Tenenbaums, it highlights the estrangement that informs all their interactions.

That said, it’s not without its flaws. The casual racism from the prior two films persists, and we’re beginning to see by this point Anderson’s strange pattern for killing pets. There are times where his shot composition suggests he prioritizes good-looking stills over moving images, as the movement of onscreen objects tends to pull the eyes away from the scene’s focal point. This is yet another pattern we’ll see emerge as Anderson settles deeper into his signature style.

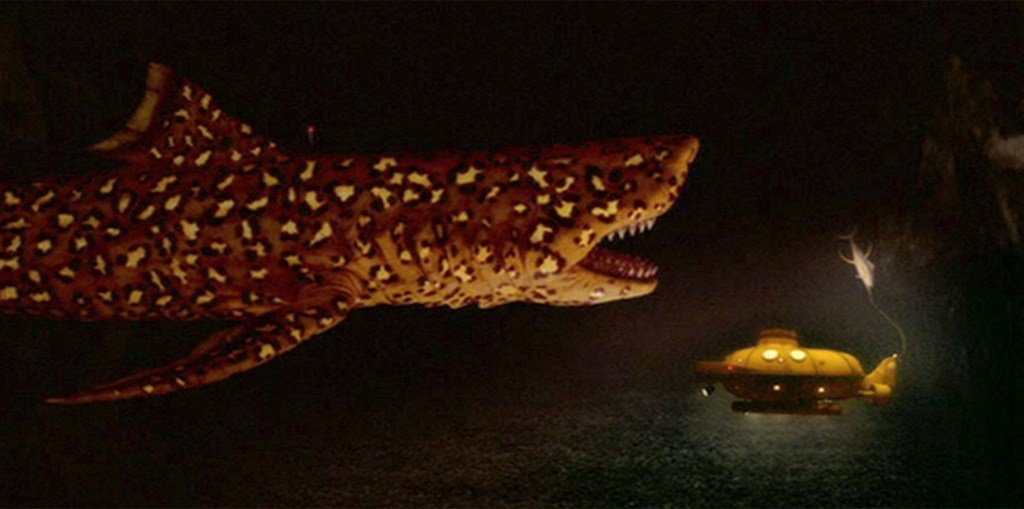

As we move into The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou (2004), it becomes clear that Anderson struggles with storytelling in general. Many of the film’s key emotional beats wind up feeling hollow, as character growth is often driven by a single line of dialogue rather than a series of meaningful events. Steve (Bill Murray) leaps from rejecting fatherhood for most of the movie to saying, “You can call me Papa Steve” without sufficient breadcrumbs pointing the way to his change of heart.

Instead, Anderson pours much of his energy into replicating the vibe of Jacques Cousteau’s documentaries, as well as creating stunning tableaus that no doubt littered people’s Tumblr feeds back in the day. Without any heart driving these images, however, we get the equivalent of a cinematic jelly baby: a brightly colored, delightfully shaped confection that disappoints with its relative blandness.

I want to make one thing clear: There is magic in Wes Anderson’s work, but it often exists in spite of him.

Which is a shame, because The Life Aquatic has what could have been a career-defining scene for Anderson: the encounter with the Jaguar Shark. It was rife with beautiful metaphor: an object of hate is seen for what it was—a magical, unique being replete with spots that both blemish and illuminate its form—and forgiven by those it wronged, drawing a direct parallel to Steve and the crew he’d hurt for so long. But because the scenes that preceded this showed no significant paths to forgiveness being taken, the impact of this scene lies mainly in what it could have been, rather than what was presented.

In short, all that beauty felt unearned.

To make things even more frustrating, the whole thing might have happened by accident. In an interview with HuffPost Entertainment, Anderson admitted that he didn’t know what the shark might have been a metaphor for, and was happy to just let others see it as a metaphor.

The remaining six films show Anderson for the filmmaker he is known to be today. It’s during this stretch where he appears to have settled on a singular voice, opting to offer variations of the same stylistic formula without truly branching off to other modes of experimentation. Even his efforts in animation—The Fantastic Mr. Fox (2009) and Isle of Dogs (2018)—are so stereotypically Wes Anderson that scenes can be spliced onto his other work and be mistaken for vignettes within the film, rather than foreign bodies.

It’s during this era where we begin to see him fully realized. Through each previous film, from Bottle Rocket to The Life Aquatic, we witness Anderson in the process of figuring himself out. There’s a clear progression towards the symmetry, palettes, and dryness he’s parodied for today.

But first, a tangentially related, though amusing aside: One unforeseen side effect of watching all of Wes Anderson’s films in succession is a newfound visceral reaction to the sight of Bill Murray. I doubt I can watch Ghostbusters again without imagining an indie folk soundtrack accompanying Peter Venkman. Some might argue this improves the film. Others might take it as the chief reason to never marathon Wes Anderson films. (There are better reasons.)

The start of the Prime Wes Anderson era is, thankfully, another film I enjoyed: The Darjeeling Limited (2007). It’s here where Anderson understands that dry humor works best when other emotions aren’t presented in the same manner. It’s hard to take what is meant to be a poignant reflection on innocence lost, for example, when it’s delivered in precisely the same way as a joke. It betrays a sense of tone-deafness, or worse, emotional cowardice—the kind where one tends to brush off a moment of genuine vulnerability with an off-tangent joke and an awkward laugh.

The Darjeeling Limited is funny where it’s meant to be, sad where it’s meant to be, and irreverent where it’s most welcome. The score uplifts the emotions of each moment rather than downplay them, and best of all, the relationship of its three leads is equal parts deliciously amusing and deeply relatable. Anderson’s meticulous composition actually serves the story rather than distract from it, letting you appreciate its cleverness without obnoxiously calling your attention to it.

All this, however, depends heavily on how well you can look past Anderson’s treatment of non-American cultures as mere window dressing to an American story. Many of the film’s Indian characters play off stereotypes much in the same way as his earlier work, and it feels as though his version of India exists primarily at the service of what is essentially a more madcap, male-oriented edition of Eat Pray Love.

These highs and lows—including some from before the Prime era—pop up so often throughout the rest of Wes Anderson’s filmography that to discuss each movie individually would be a waste of space. The same problematic American-ness is found, for example, in the woefully racist Isle of Dogs, where Japanese characters are inexplicably othered in their own setting, their culture an excuse to include borderline racist gags while an American exchange student-cum-white savior drives the plot forward. The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014), though his finest work in that all the Anderson-isms actually enrich the viewing experience, touches only lightly on the historical fascism that ruled over Hungary at the time the film was set.

The Fantastic Mr. Fox completely revamps Roald Dahl’s source material such that the author’s presence is no longer felt; instead, we have a slightly more mature version of Bottle Rocket’s Dignan as our titular hero, complete with the same lack of growth. Moonrise Kingdom (2012) manages to find some charm in the romance between its two young leads, but it’s buried underneath Anderson’s distracting composition and all-too-convenient character swerves.

Though it may be unfair to accuse Anderson of favoring style over substance, there’s a case to be made for the style overwhelming the substance.

I want to make one thing clear: There is magic in Wes Anderson’s work, but it often exists in spite of him. Underneath all these frustrating elements, the inexorable sameness of his imagery, the absolute disregard for the basics of visual storytelling, is someone with a profound understanding of his own humanity, limited as his lived experience may be.

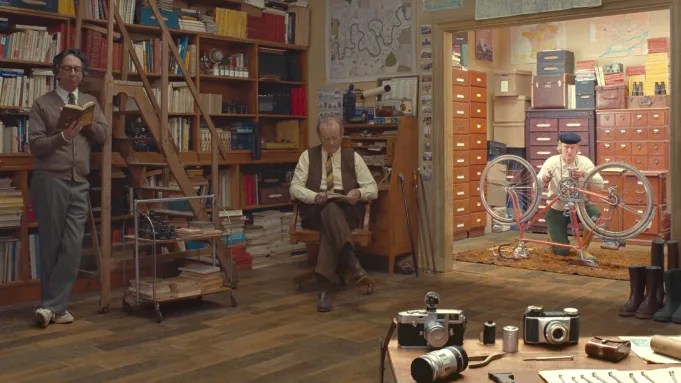

His tenth film, The French Dispatch (2021), is perhaps the best example of this, and of why I don’t think this 16.5-hour long sojourn into his worldview has convinced me to like him.

It is, at its core, a love letter to stories. The French Dispatch is an anthology that brings to life each section of the titular publication’s final issue, with each chapter being told through the eyes of a different author. It waxes nostalgic for a time when most writers lived through their stories, rather than borrowing from the experiences of others online. It longs for the long-drawn romance between the writer and their craft, where one’s own words weren’t beholden to the tyranny of metrics.

All The French Dispatch’s editor-in-chief (played by Bill Murray, big surprise) cares about is a story well-told, even as his ragtag team of writers stray egregiously far from their assignments. This is where I finally find some common ground with Anderson.

The problem is, the film doesn’t quite tell its own story that well. The authors, though diverse, sound almost exactly like each other in the rhythm of their lines, in turn sounding much like the protagonists in Anderson’s previous films. Visually, it’s Anderson at his most detail-oriented and most scatterbrained, constantly dragging the eyes away from key focal points. Though it may be unfair to accuse Anderson of favoring style over substance, there’s a case to be made for the style overwhelming the substance.

Which is a shame, because as a writer, I wanted so badly to love a film that, on paper, appears to have been written for me. Instead, I feel as though the act of communication is a bother to Anderson, that he prefers to speak for me rather than to me. There is magic in this film, too, but it’s a smug, selfish sort of spell, enchanting you only ever so slightly because it refuses to meet you halfway from its caster.

And now, having sat through all his films thus far, I have to ask myself again: Do I finally understand the appeal of Wes Anderson? I’d like to think so.

Objectively, there is much to enjoy. His visuals, though not always effective, are rich, vibrant, and inspiring in their aesthetic. His dialogue is forever clever, regardless of the flatness of its delivery at times. Though he hardly ever strays too far from his trademarks, he is always playful with them. All these are valid reasons to admire him.

But I’ll admit that his greatest strength was the one that proved me wrong. In my notes for this marathon, I accused Anderson of cowardice. I’d believed that he was afraid to get too intimate with his audiences, resulting in emotionally distant work. While I still believe that majority of his films are indeed much too cold for my liking, I was mistaken in calling him a coward.

What Wes Anderson is best at is putting himself into every single frame of his films, in every page of his scripts, in every questionable choice he makes. This, in my view, is his appeal:

Wes Anderson is, for better or worse, the very best at showing you Wes Anderson.

Emotional distance exists in his films not because Anderson is afraid, but because that is how he experiences the world. The details often get in the way of his storytelling because that’s just who he is. His films are homogenous in their idiosyncrasies because to shoot them differently would be to lose sight of Anderson himself. There is genuine bravery in how unflinchingly he represents himself through his work, detractors be damned.

It’s not as though Anderson is dumb to the criticisms hurled at him, either. Every now and then, we’ll see him make direct responses to his critics: crafting a story that touches on the horrors of animal testing after coming under fire for the many pet deaths in his work, or casting Tony Revolori as his lead after audiences noticed the glaring whiteness of his films. The improvements are, however, secondary to his self-expression, which is why these responses often fall just short of satisfactory to viewers like myself.

And he knows that, too. He is far too smart and far too self-aware to be that ignorant. We know that because every single one of his protagonists, even in his earliest films, is quite clearly a reflection of Anderson himself.

Like Steve Zissou, he is aware of his faults and unsure of how best to fix them. Like Royal Tenenbaum, he is entitled and sexist and racist, but not maliciously so. Like Max Fischer, he is remarkably clever and insufferably cognizant of that fact.

Like Dignan, Wes Anderson is difficult to love, yet people love him anyway.

Or they don’t.

And, as it goes for many of Anderson’s characters, that’s okay.