Approx. reading time:

There’s a lot of talk about the generational divide in workplaces, where older generations constantly clash with younger ones over different things. Boomers don’t know anything. Millennials don’t want to work. Gen Z is too obsessed with labels. Where the hell is Gen X?

This conflict between generations can often lead to dwindling productivity, lower morale, and just a generally unpleasant atmosphere at the workplace. And with people being a lot more outspoken these days, the gap just gets wider.

But here’s the good news: in order to address the generational divide, you can try to establish generational flexibility in your workplace.

For the purposes of this article, we’ll define generational flexibility as “a workplace’s ability to facilitate knowledge-sharing between cohorts of different generations, and adapt its environment accordingly.” Generational flexibility allows a company to adapt quickly to the times and to new perspectives, all the while building foundations that foster solidarity between co-workers.

And the key to practicing generational flexibility lies in how we engage our interns.

In most offices, interns are relegated to grunt work—getting coffee, running to the printers, encoding mountains of boring data. While they do learn valuable soft skills in relating with established employees, most of what they learn in terms of work lies in the realm of institutional memory, which they more often than not end up unlearning after graduation.

Institutional memory is an organization’s pool of knowledge earned from its years of experience. It’s any given company’s core concepts, workflows, and best practices. What we fail to realize is that every institution is unique; what may be a best practice for one company won’t necessarily translate to a different work environment.

By focusing solely on downloading our institutional memory onto our interns, we essentially put them in a box. They’re taught that our way is the only way, which severely limits their flexibility, adaptability, and sense of innovation. Then, when they get hired by a different company—which is the case for most interns—they’ll have to discard anything we teach them in order to fit into their new employers’ processes.

What we should be doing instead is creating an environment where they can use institutional memory as a foundation for innovation. This is where the knowledge-sharing part of generational flexibility comes in.

Let’s say your company catalogues receipts by date, because that’s how it’s been done for years and, quite simply, it works. And so, you teach your interns to continue sorting receipts by date, as you’ve been doing for years.

But what if they found a way to make this process better? What if sorting them alphabetically actually makes the receipts easier to find? Most interns won’t have the courage to speak up for fear of rocking the boat, which often ends up in companies missing out on these learning opportunities.

This is why you may want to try holding a session at the end of each week asking interns to evaluate the processes in which they’ve been included. Ensure them that this is a safe space for them to express their opinions, and that there are no wrong answers. Allow them to suggest innovations within the existing paradigm.

Then, working with your institutional memory, explain to them how these suggestions may or may not be feasible for this particular company. You may have learned, for example, that alphabetical sorting doesn’t quite work as-is when your company issues receipts to 11,000 people named “Juan De La Cruz”.

Note that I said “as-is”; just because an idea doesn’t mesh with your company on its own, it doesn’t mean it can’t be tweaked. If you see the value in your interns’ suggestions, discuss with them how you can adjust them so that they are built upon your institutional memory rather than demolishing it. Perhaps having a nested cataloguing system, where receipts are sorted alphabetically first, and then by date, would result in a much more streamlined workflow.

The key is to be flexible in your operations, allowing room for giving new ideas a shot, especially if they come from younger generations.

This sense of flexibility between generations results in a win-win situation for all parties—not only are your company’s systems improved, but your interns learn valuable lessons in innovation and cooperation. Showing them that an established employee can be humble enough to learn from interns also plants seeds of the same type of humility among them, encouraging a culture of learning wherever they go.

When there’s no hierarchy among generations,

team members are more likely to be supportive of each other.

This type of mutual mentorship shouldn’t be limited to just work processes, either. If you want to practice true generational flexibility, you might want to do a similar knowledge exchange when it comes to culture, as well.

There are major cultural shifts in every generation, both in terms of the workplace and beyond it. While baby boomers believed in climbing up the ladder of a single company and reaping the rewards of tenure, millennials started the trend of job-hopping, where tenure becomes secondary to personal fulfillment. Gen X may be more accustomed to learning through trial-and-error, as this was the generation that saw a rise in a more hands-off approach to parenting; Gen Z, on the other hand, grew up with access to millions of YouTube tutorials, making them excellent self-learners with less need for practical experience.

Whereas baby boomers and Gen X are more likely to adhere to heterotypical gender norms, millennials and Gen Z are much more liberal when it comes to defining one’s gender and sexuality.

All these factor into a company’s culture, and the strict adherence to one perspective over another is what leads to friction between members of different generations. “Culture wars” begin when there are no attempts to bridge the generational divide.

But the truth of the matter is that every generation has something valuable to learn from all the others. People should be able to complement the benefits of tenure with personal fulfillment. Learning is most effective when you blend video tutorials with practical trial-and-error. By asking your interns to teach you about what makes their generation tick, you set the foundations for a culture that welcomes them when they finally enter the workforce.

At Journalixm, for instance, we ask each of our interns to draft articles written exclusively from their viewpoint as people. Not only would it be hypocritical of us to ask otherwise, being a publication driven by sei-katsu-sha, but it also allows our own team to gain insights into what the coming generation values.

We’ve learned that they care deeply about our planet, are more interested in online media than traditional media, and believe in achieving success at one’s own pace. On the flipside, they’ve learned from us the value of staying up-to-date on current events, how being fearless with one’s personal insights is worth its weight in gold, and how some discussions can be more efficient over calls than over chat.

This free exchange of knowledge and values also results in something that every business could benefit from: solidarity. Because interns are treated as equals to employees, there’s a greater sense of personal responsibility towards the group. When there’s no hierarchy among generations, team members are more likely to be supportive of each other. If you have your interns’ backs, they’ll have yours.

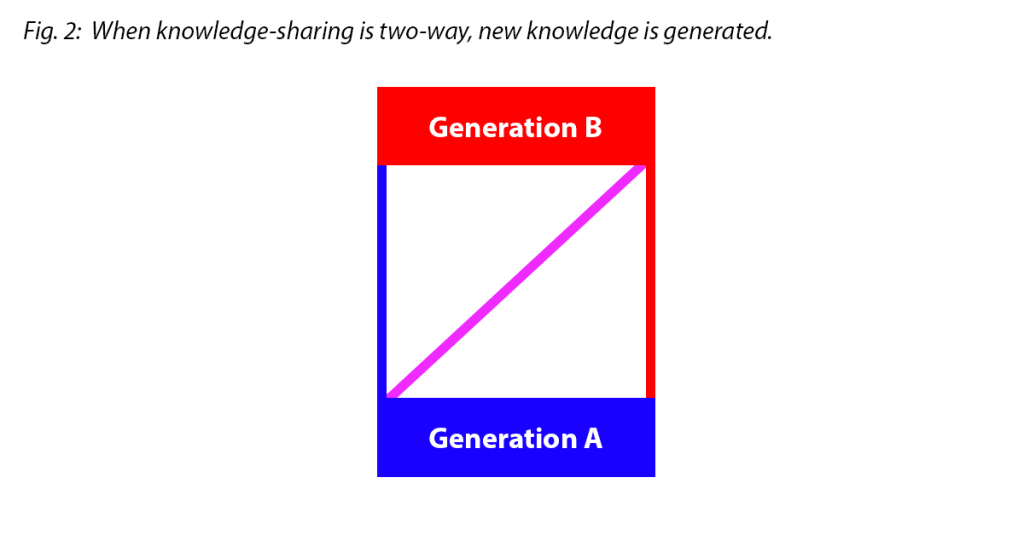

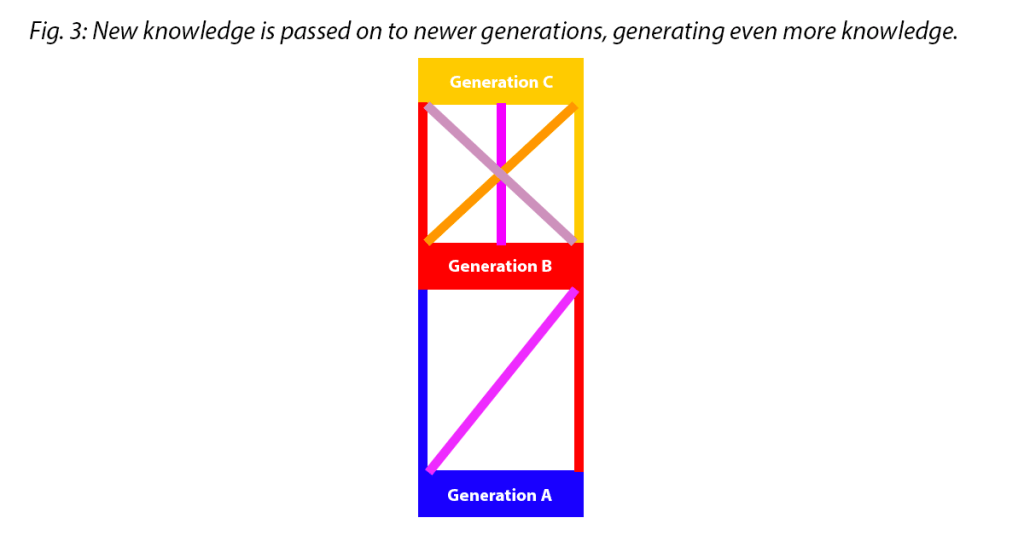

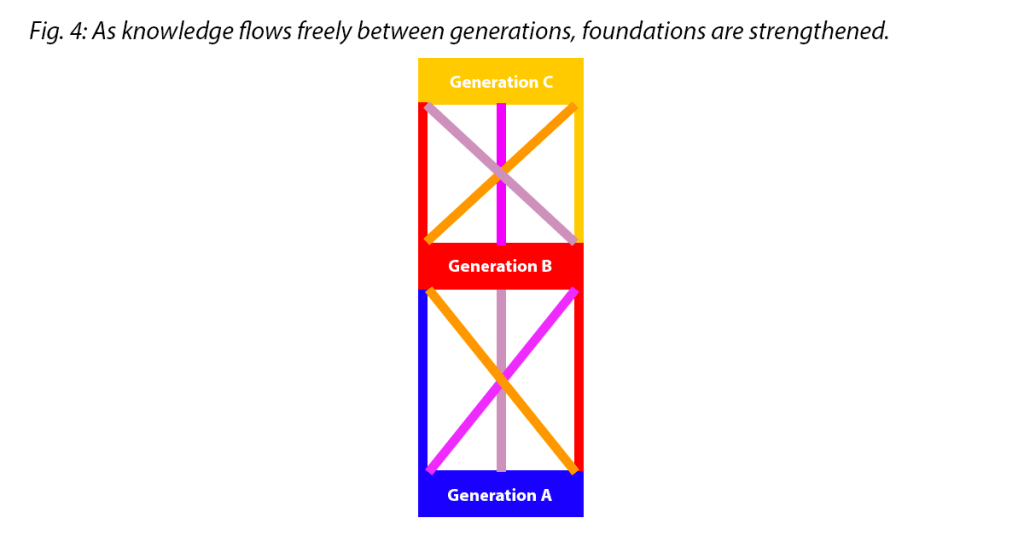

Perhaps the best way to demonstrate all this is with these diagrams, where each box is a generation, and each line is that generation’s knowledge and values:

When the older Generation A simply sends its knowledge (the blue line) to the younger Generation B, we don’t really create much of a solid base. Everything is supported only by what Generation A knows.

If Generation B is given the opportunity to share their own knowledge (the red line) with Generation A, however, not only does the knowledge base become more stable, but new knowledge created by this cooperation (indicated by the purple line) helps strengthen the foundation being built.

When Generation B starts sharing knowledge with the even younger Generation C, they pass on both their own knowledge and the new knowledge created with Generation A. This, in turn, creates two more new lines of knowledge (indicated here as the orange and mauve lines) that create a rock-solid knowledge base on their tiers.

In a generationally flexible workplace, all these new ideas are also shared with Generation A, resulting in foundations that continuously get stronger with each new generation that enters the system.

In short, freely sharing knowledge—in all its forms, from skills-based to cultural—between generations makes a team stronger. The sooner we allow younger generations to participate in an equal exchange of ideas and practices, the more dynamic, and therefore future-proof, our workplaces will be.

The more we practice generational flexibility, the better our foundations become.

Interns are essentially a preview of our next generation of co-workers. It only makes sense, then, that in order to practice generational flexibility, we need to start learning from our interns as much as they learn from us.