Approx. reading time:

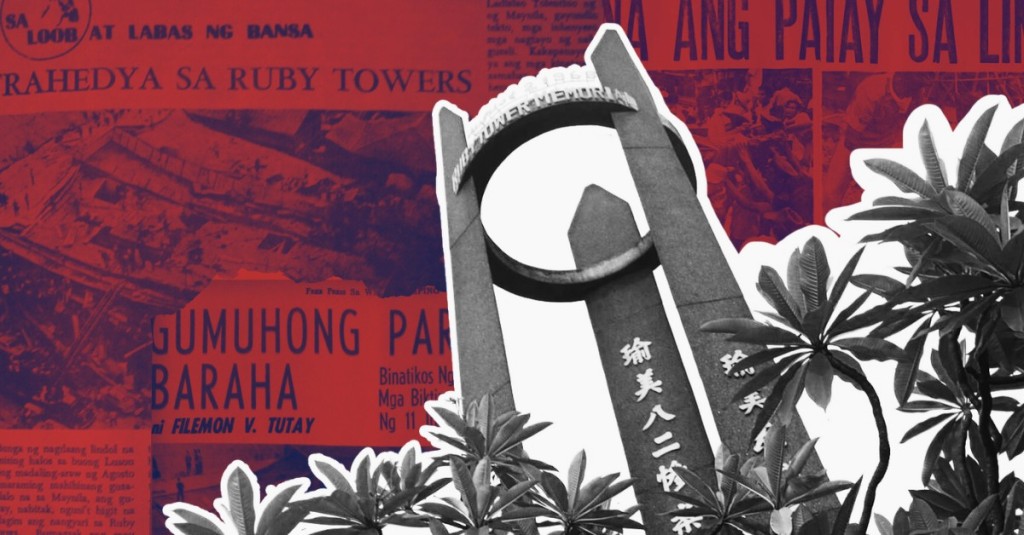

The Chinese Cemetery was solemn, but Manila’s urban sprawl led right up to its gates. Inside, sitting in a quiet corner, was a two-storey memorial with three prongs jutting up to the sky. Most of the writing on the memorial was in Chinese. The date August 2, 1968 was proclaimed on top.

I drove right up to it and parked, playing the only radio broadcast that aired live on the morning of that day.

Famed radio host Johnny Midnight was on DZAQ (now DZMM), interviewing a doctor about the death of then-Secretary of Health Paulino Garcia by heart attack just two hours before. Then, for a minute, the broadcast went quiet. When Johnny came back on the air, calls were coming in so fast, he barely had time to react. People were calling in about power outages, fires, water stoppages, and more. His show became an impromptu disaster coordination center, as it was the only one that managed to stay on-air in Manila throughout the chaos.

It was a little after 4 AM when one of the strongest earthquakes in Philippine history hit without warning. The epicenter was in Casiguran, Quezon (now Aurora), but the quake was strong enough to cause tsunamis as far as Japan. Later on, we would learn that it was a 7.3-magnitude quake, and registered a VIII (“Damaging Tremor”) on the Adapted Rossi-Forel Earthquake Intensity Scale. While Casiguran was struck the hardest, it was Manila that experienced the most casualties.

Johnny Midnight was fielding calls from Manila, Quezon City, Pasay, and Subic Bay, among other areas. The host reckoned that the aftershocks lasted for around five to seven minutes after the initial tremor. As he urged his listeners to stay calm, he couldn’t help but let a moment of doubt slip: “I hope there’s no more of this.”

Although the available recording didn’t capture the moment, Johnny eventually received word of a massive tragedy: Ruby Tower, on the corner of Doroteo Jose and Teodora Alonzo streets, had completely collapsed during the earthquake.

Ruby Tower was a posh six-story apartment building in Binondo. It had commercial spaces on the ground floor, and 76 apartments stacked on top. It was a place for people to come together; middle-class Chinese-Filipino families, wealthy customers, employees, and staff all occupied the tower throughout the day.

There was no real chance of escape when the Casiguran earthquake struck; most of the tenants were asleep. The building shook and crumbled. The upper floors collapsed, leaving the entire south side of the building in ruins. Witnesses said it was like seeing it pressed down by a large invisible hand. Hundreds were trapped in the rubble. People reported hearing voices from under the debris calling for help.

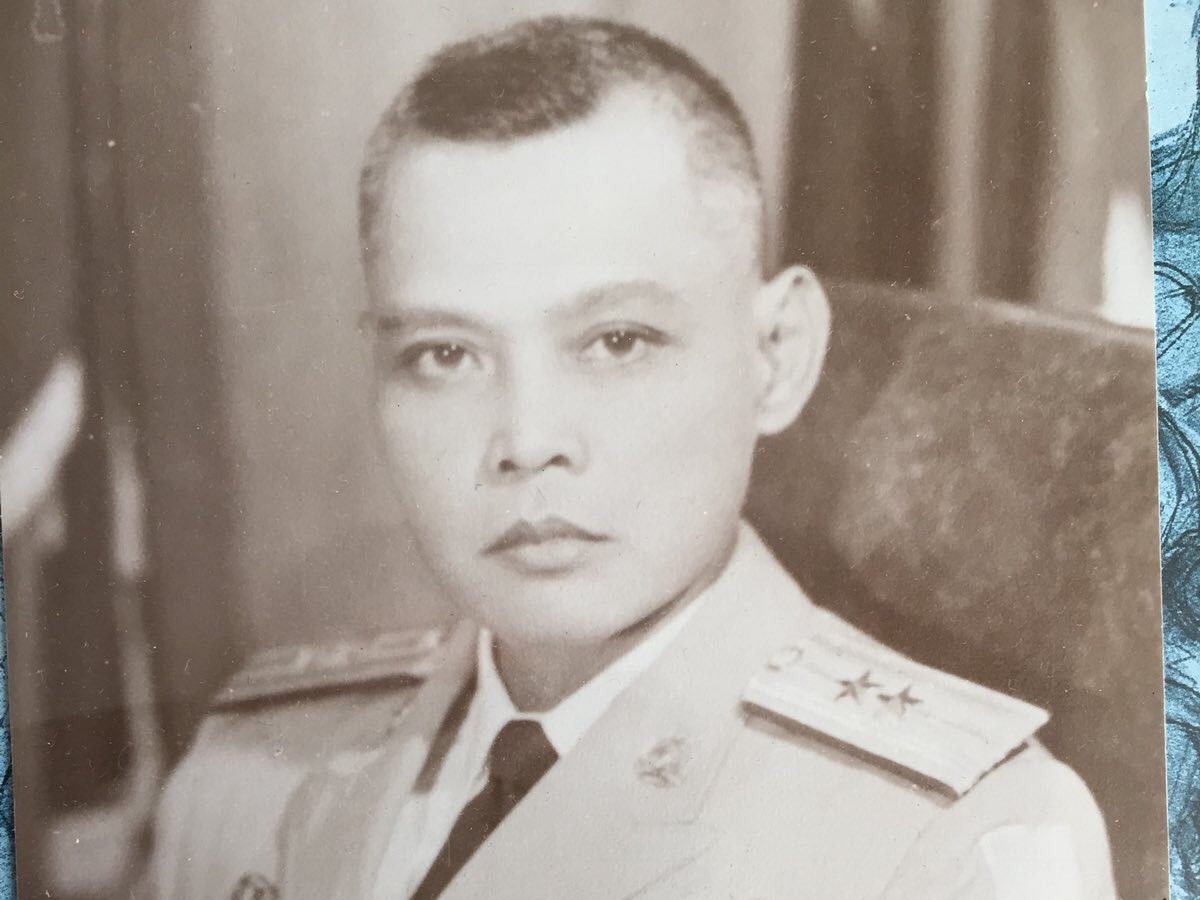

As day broke, another host took over for Johnny Midnight to continue the broadcast, now supplemented by round-the-clock television coverage via ABS-CBN, which owned DZAQ. Over the next few days, the news would cover an international rescue effort led by Major General Gaudencio Tobias, who had just returned from leading the Philippine Civic Action Group (PHILCAG) in Vietnam just two weeks prior.

“This is more tragic than anything in Vietnam because it is peacetime,” he told reporters.

The rescue process was slow and difficult. The heavy equipment could only access one side of the building, which meant the bulk of the work had to be done by hand. People used jackhammers and drills, constantly worried about the structure caving in further. Rescuers found themselves being guided by the screams of survivors trapped in the rubble.

Both Teodora Alonzo and Doroteo Jose streets were crammed with people. Thousands came to help the relief effort. 6000 people congregated to dig, administer first aid, and comfort the wounded. There was a command center set up in the nearby Arellano High School staffed with medical professionals and more volunteers.

But as time went on, things grew more grim. Tobias had hoped to finish the operation within 72 hours; any longer, and the odds of finding survivors dropped exponentially. On the third day of rescue efforts, his fears were confirmed. The wreckage of Ruby Tower was beginning to fill with the smell of death.

“During the early phase of the search operation, the ratio was six survivors to one dead,” Tobias said. “It is now six dead to one survivor.”

Still, Tobias and the rest of the operation persisted. Despite the dwindling numbers, there were stories of people being pulled out of the rubble with minor injuries. Several children came through; some protected by their parents’ bodies. Workers wept when they pulled out three little girls who kept each other alive by huddling together. Suzie Wong Chan and her cousin Nancy Wong Chan were trapped in the rubble for over 120 hours, but somehow managed to hold on. Upon being rescued, Susie begged the doctor in several languages not to let her die. She survived.

Rescue efforts ceased August 9, 1968. The final count: 268 people dead, and 260 people injured.

On December 2, 1968, the National Committee on Disaster Operation was established; it was the precursor to the National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Council (NDRRMC) today. When Ruby Tower collapsed, there was no disaster agency to coordinate the rescue efforts, which resulted in the loss of precious time. The NCDO was created to ensure that next time, there would be a clear line of authority.

ABS-CBN, bolstered by its success in delivering real-time updates on the disaster to its viewers, would continue to expand its ability to cover breaking news. DZAQ shifted to the 24-hour news format we know today as Radyo Patrol.

Most importantly, the fall of Ruby Tower sent a message. The tower was only 3 years old—the buildings around it survived the quake. So why did it collapse?

The answer is simple: greed. The concrete used was cheap and subpar, the beams didn’t have the right ductility, and the rigid structure was not built to withstand a quake of this magnitude. There had been no soil erosion study to ensure the building foundations were supported properly; they gave way as soon as the shaking started.

Up until this time, building codes in the Philippines were not standard. There were different offices that needed to approve the plans. There were geological surveys that needed to be done, and specific safety precautions that should have been taken, but they were not consolidated, making it easy for contractors to take shortcuts. It was cost-cutting measures like these that ended up being the reason behind the collapse of Ruby Tower.

The company behind Ruby Tower, Solid Tower, Inc., built the tower according to the plans of an inexperienced architect named Tito Plamenco. He created the plans, but refused to sign the documents. Plamenco was told his plans were for marketing purposes. Another architect named Raymond Garcia ended up signing them over Plamenco’s printed name.

After the rescue efforts had ceased and the dust had settled, people were looking to hold someone accountable, but Solid Tower, Inc. settled the case. The victims were given the land on which Ruby Tower stood and were appeased. The investigation was stopped once it became clear that negligence and corruption at all levels were to blame.

It’s hard not to get frustrated with this story because, for such a tragedy, it seems preposterous that no one was actually punished. The fall of Ruby Tower tells us that shortcuts and cost-saving measures trumped our respect for proper guidelines, and it resulted in the loss of 268 lives.

The National Building Code was passed to protect people against this happening again, but only officially so in 1977—nine years after Ruby Tower’s collapse.

Back at the Chinese Cemetery, the memorial is smaller than I expected. The plants are overgrown. One of the locals told me about the disaster, but was too young at the time to remember most of the details.

The Casiguran earthquake lasted for 44 seconds. That’s all it took to bring down Ruby Tower.

Now, 55 years later, we have building codes in place to ensure this doesn’t happen again. On top of those, we also have a disaster relief agency to warn us of upcoming hazards, and to coordinate the rescue effort when something happens. We learned some lessons, but they fall short when you realize the whole story—the story of a company that prioritized savings over safety—was swept under the rug.

I stood for a long time staring at the faces of the people who died in the quake. I am not a spiritual person, and yet I felt ashamed that I didn’t bring an offering. These people perished because of someone else’s negligence. They trusted that the building that sheltered them would stand the test of time. They died because someone else wanted to save money.

What is the cost of human life? Could any amount of savings possibly make up for the trauma, the broken families, and the tragedy?

A memorial is not enough. Appeasement is not enough.