Approx. reading time:

With Gilas Pilipinas falling to a 0-4 record at the 2023 FIBA World Cup, armchair analysts have started creeping out of the woodwork, spouting the oft-repeated argument that the Philippines simply isn’t built for basketball and we should just give up. These opinions are objectively wrong; in fact, Filipinos can and should thrive in the modern game. Here’s why:

1. Height doesn’t matter as much anymore

The argument that Filipinos are too short for international basketball is grossly outdated. Team around the globe have been embracing the “small-ball” concept since the Golden State Warriors won the NBA championship with the 6’6″ Draymond Green as their center. To put that into the local context, he’s the same height as PBA legend Danny Ildefonso. Steph-freaking-Curry is 6’2″, which is the same height as Allan Caidic and James Yap.

In the NBA alone, the average height of centers and power forwards has dropped to 6’8″ to 6’10” today, putting the likes of June Mar Fajardo and Japeth Aguilar in that range. The Euroleague’s three most recent MVPs—Sasha Vezenkov, Nikola Mirotic, and Vasilije Micic—are all 6’10” and shorter.

What sets most of these players apart from our own is the skillsets they’ve trained for. While we still stick to idea of fixed positions, the rest of the world has moved on to position-less basketball, a paradigm for which former Gilas coach Tab Baldwin has strongly advocated.

Our centers, for example, still more or less stay close to the basket on offense, using their height to gain an advantage over other players. In international basketball, however, this style of play is slowly dying, as big men today are expected to be more mobile and able to shoot from further out. It allows players to move the ball around more freely on offense, which in turn exhausts the defense as players try to cover more ground.

We should be training our tallest players to be more versatile on the court. Rather than forcing a 6’8″ Filipino to stay close to the basket simply because he’s bigger than most of his competition, he should be developing the guard skills that 6’8″ players across the globe are using to great effect. Why try to develop the next Asi Taulava when we could have a Filipino Boris Diaw or Draymond Green? There is absolutely no reason that we can’t have an effective small-ball lineup of our own.

The game today is all about movement, reading the space it creates, and reacting accordingly. Our national team unfortunately isn’t trained for that, which is why we’ve fallen behind everyone else. Thankfully, this is more easily corrected than we think, and all we have to do is look at kalye ball.

2. Kalye ball is a surprisingly decent starting point for the international game

The games we see being played on our streets and in barangay basketball courts tends to be more position-less than those in professional leagues because… well, it’s generally harder to find someone 6’3″ and taller among average Filipinos. Without many glaring size advantages dictating matchups, there’s a stronger emphasis on ball movement on both the individual and team levels.

In street games, space is at a premium, forcing players to favor shifty, economical movements and improvisation. The internationally recognized Pinoy Step maneuver, for example, can be seen quite often in kalye ball because it can create last-minute separation between the ball handler and their defender in tighter spaces.

This is invaluable in the modern game, where defenses are designed to prevent player movement in general. Being able to lose one’s defender despite a seeming lack of options separates good scorers from elite ones.

Barangay leagues, on the other hand, are often transition-heavy while favoring do-it-all players who can make split-second decisions. While in amateur situations, this often leads to the players’ teammates being all-too happy to let their “stars” do all the work, the emphasis on the stars’ decisional flexibility in uptempo situations is what position-less basketball is all about. But a team where every player shares that same versatile mindset is the type that excels on the world stage.

This isn’t to say that kalye ball will save the Philippines, mind you. While improvisation and flexibility are crucial, they don’t get players anywhere without a cohesive system that puts these skills to good use. It’s just a starting point for something far more valuable than any player or coach: a proper player development system.

3. Accessibility determines development

As it turns out, the Philippines is also uniquely positioned for that. We have courts virtually everywhere, and simply being able to play is the first step towards developing basketball skills. That shabby barangay court with plywood boards half-eaten by termites and rusty hoops is still a facility anyone can access if they want to learn, play, and practice basketball. In this writer’s personal experience, it was often harder to find someone with a good ball than it was to find a court, and that certainly says something about the sport’s omnipresence in this country.

This already gives the Philippines a leg up on improving its player development system. These courts need to be repaired and/or upgraded, and used for basketball camps that both allow players to learn new skills and allow teams to scout for promising new talent nationwide. This widens the net our national team can cast in their search for local players, instead of relying on less-accessible collegiate and professional leagues, or on lower-rung international talent willing to play for us.

Of course, accessibility is only half the story here. Facilities and training camps are only as good as their teachers, so instituting a proper player development system will cost a significant amount of money. Which, again, is no problem.

4. Pinoys love to spend money on basketball

The main reason basketball in the Philippines gets significantly more support than other (arguably more deserving) sports is because sponsors make more money from it. Sports are dependent on painfully capitalist systems, and while I personally believe this shouldn’t be the case, it’s the reality our athletes live in. What is absolutely baffling, however, is how far we’ve fallen behind the rest of the world despite the inordinate amount of financial support our basketball players enjoy compared to others.

The problem here is that the money is likely going to the wrong places. Our national team system spent a significant amount of money to naturalize Andray Blatche, who wasn’t exactly a stellar player during his time in the NBA. We’ve also invested a lot of time and money into flying in Utah’s Jordan Clarkson. It’s almost as if we’re trying to buy talent instead of developing it, and this is detrimental to Philippine basketball in the long run.

And it’s not like this system works, either. On a fundamental level, basketball is a team sport, and teams are built on chemistry and cohesion. Players need to train together on a regular basis in order to learn each others’ strengths and play off of them. Bringing in a star who joins the team two weeks before the competition kicks off throws all notions of chemistry out the window.

Instead of spending all this money to scout for players abroad, we should be investing in a national team system that allows players to gel together. This means getting players who reside in the Philippines rather than elsewhere, so they can be available for regular training sessions with the rest of their teammates. Modern position-less basketball requires teams to be of one mind; it’s hard to cultivate that when some players live an ocean away.

And it’s not like we’re at a shortage of local players willing to put the time and effort into being part of the team, either. Basketball is, after all, a national obsession.

5. There’s no substitute for passion

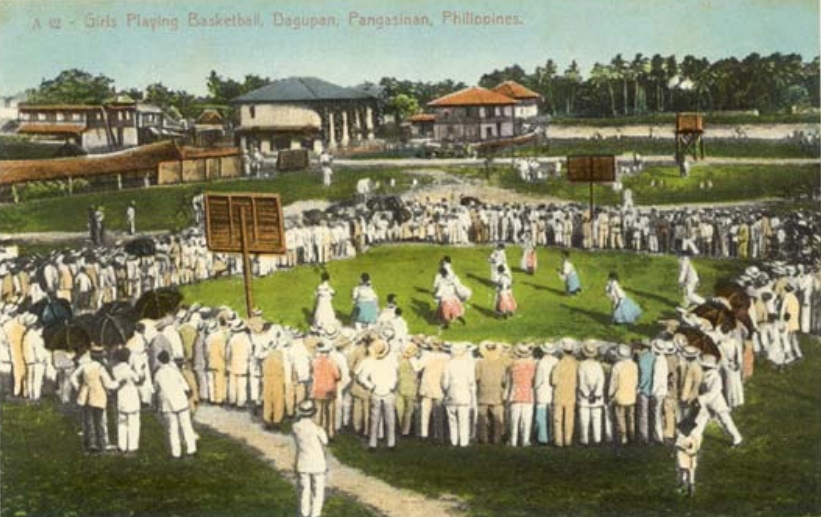

Critics are vocal about Gilas’ shortcomings because above everything else, we are a country that wants to win at basketball. It doesn’t make sense, but it doesn’t have to—we love basketball, period. We’ve loved this sport for more than a century. That deep-rooted passion for basketball is what provides the impetus for every improvement our national team needs to make.

And yes, there are other sports we should be passionate about, too. That doesn’t mean that we should drop basketball entirely; that just means we have more sports to love. There’s nothing stopping us from supporting Gilas and our National Women’s Football Team, EJ Obiena, Hidilyn Diaz, Carlos Yulo, and everyone else at the same time. In fact, we should support as many Filipino athletes as we can—and that includes our esports athletes!—because sponsors go where fans go. The more we support our athletes, the more likely it is for them to get the funding they need to excel.

Basketball is just in a prime position in this regard because it’s already got a thriving fanbase in this country. There is no imaginable way that Filipinos will ever fall out of love with the sport, so why not run with it instead? But if we want our passion for basketball to be rewarded, it all comes back to doing things right.

6. We already know what to do

As loud as the critics calling for the abandonment of Philippine basketball are, equally loud are the people who have good ideas on how to fix it. It’s just a matter of getting the people in charge to listen.

What do we need, exactly? A training system that fosters homegrown development, which in turn allows us to build a national team that practices regularly enough to form genuine team chemistry. We need coaching that evolve beyond the isolation-heavy schemes that dominated the 90s and early 2000s, and adapts the dynamic position-less basketball paradigm that’s been dominating international play. We need sponsors who are willing to spend on the right things: upgraded local facilities, training camps, and player welfare.

And most of all, we need the fans. We need people to continue supporting Philippine basketball, but not blindly so—we need the kind of support that demands that things are done the right way. We need a fanbase so fueled by its passion that the people up top have no choice but to change things for the better.

Sa puso nagsisimula ang lahat ng pagbabago.