Second of a three-part series. Read part one here.

by Wilfredo Pascual

Approx. reading time:

One of my most reliable writing rituals is asking my husband to listen to me talk about a section I’m working on—a nebulous idea, an ovulating story. I give myself a time limit if he’s up for it, two to three minutes. He knows it’s not for feedback. It’s brief, but I get so much out of this. Not only do I get to hear my thoughts aloud and shape them, but I also get to map the section I’m working on, the emotional beats, peaks, and valleys.

I admire sentences and writing that precisely convey emotional tones you don’t hear often. This is what we do as writers. We toggle between meandering and efficiency in our writing. Is this the best way to get from point A to point B? Is there enough muscle? Is this the part where it needs to breathe and radiate? How do I know I’m not just showing off? And which parts do I let go so that the rest can do what it needs to do? It’s more than just technical proficiency. Alam mo, I recently told my husband, I can write this section na sobrang dali at sobrang perfect, pero hindi ko siya maatim kasi it feels stale. Hindi siya alive kasi wala nang multo.

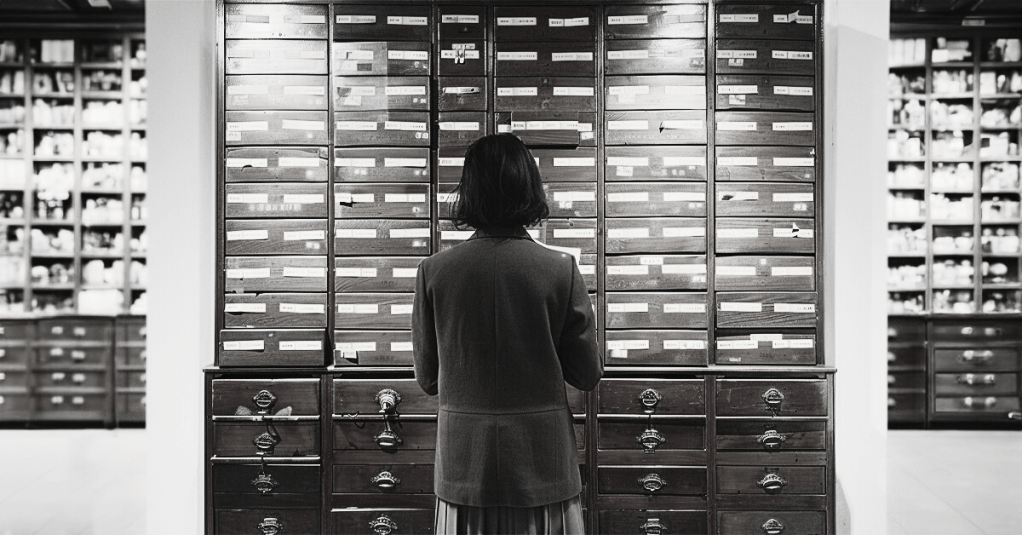

In Pale Khakis with Dark Socks, poet Wayne Koestenbaum wrote about writing a novel in tiny paragraphs, which made me think of how some of my essays take form. Imagine a big cabinet inside your brain with tiny little drawers for your writing. This is where you will keep your relics, artifacts, specimens, etc. Resist the urge to curate them. In fact, make sure they don’t talk to each other. And do not check on them every day. The trick is to be judicious in growing your collection. Your personal essay has numerous entry points. Emotions, ideas, narratives. If you don’t know where to start, you’re probably in a good place. Now a pick a random drawer. See if any item has grown legs or acquired a new language, a new way of speaking, then listen and follow them. Start with a clear sentence.

You have tools and then you have process. So many ways to tell a story, a lifetime to explore. You can go cinematic, linguistic, thematic. You can go for shy phrases, the impressionistic, the oracular details. There is no template. The process is where you get to be you, the emotional string you hold on to inside the labyrinth.

There’s a dial I turn in my brain that zooms in and out across timelines. I noted this recently, the value of nurturing timefulness in my personal essays. It humbles me, demands that I frame my work on a continuum, an evolution. I can revisit the same essay across years, and other stories would latch on to it—old essays, radical forms of understanding, new spaces for feeling and breathing, its elements radial and fractal.

I was fortunate to be right-handed. My left arm and hand were so stiff it took another three months for my hand to regain its dexterity and function again. On April 24, 2024, my surgeon studied my x-ray results and congratulated me. Still there, he said, all the hardware aligned. 172 days after my accident, the fracture is healing well. In some parts you can’t see the break anymore. He will see me again in three months. I’m still not allowed to carry more than five pounds with my left arm, nothing heavier than a two-liter soda. When he first saw me, he told me they don’t often get major injuries like mine in Marin County. He was a young orthopedic surgeon. Healing broken bones to him was like his art. He was proud of my progress.

The occasional pain was short and tolerable, but managing the weight of the long arm cast was exhausting on so many levels, and the dreadful itch was punishing. There were nights when I worried that I would lose it. I wanted to take off the cast. The helplessness was crushing. There was nothing I could do but turn once more to writing for solace and sanctuary. The writing was slow, but slow was good. It felt right and soothing to be doing what you were supposed to be doing.

The body has its own memory too. I stayed in during my recovery, which coincided with the winter storms, listening to my body, the earth. I wrote a sequence treatment and sent out four essays. This is the first essay I composed and typed with two hands since my injury.

When I was fourteen, I kept a diary with a blue satin ribbon marker and my favorite Sanrio characters on the glossy laminated hardcover. Kiki and Lala, mystical twins from the Star of Compassion, wondered about life on earth. They loved to draw, write poems, and fish for stars in their long-sleeved white gowns. They braved the long journey to earth. Always, the two: one curious, the other protective. One day, I caught my classmates huddled around my desk, reading my diary. I had stepped out during Algebra break, and was horrified to see them craning their necks, their eyes scanning a page, letters I wrote to God about my repressed sexuality. Putang inaaa! I shouted at everyone and no one.

I grabbed my diary and ran out of the room, past the hall, shaking. I ripped the pages, tore its spine, and threw it in the trash bin. I ran along an empty avenue under towering canopies of acacia and mango trees until I reached the main gate of Central Luzon State University. I realized what an idiot I was. I ran back to the science high school building, but it was too late. I saw other students walking away from the trash bin with torn pages.

It was a powerful moment in my life as a young writer. I brought home the rest of the diary and stuffed its crumpled pages in a hole in my mattress. Some of our most potent writings have words that come from this secret place, writing as tender as our softest organ tissue. Others are passages of grace and defiance on what it means to be relentlessly human. Many speak to different kinds of hunger and freedom. I swam in strange emotional currents, attuned to the anomalous in my young writing life.

Wilfredo Pascual grew up in San Jose City, Nueva Ecija. He worked for 20 years in the international nonprofit space before settling in San Francisco, USA. A multiple Palanca winner and Ani ng Dangal awardee, his essays have earned a Pushcart Prize nomination and a notable citation in the Best American Essays. He has been published in the Philippines and abroad, with his latest work forthcoming in The Kenyon Review.