by Wil-Lian L. Guzmanos

Approx. reading time:

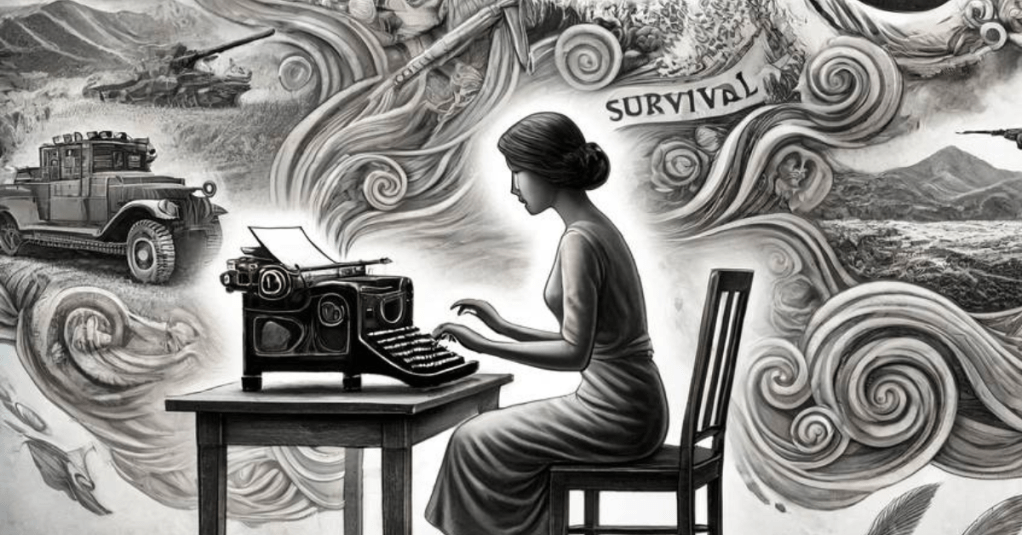

My great-grandparents and grandparents were refugees from Amoy, China during the Second World War. All members of the clan were massacred or perished shortly after, save for my maternal great-grandparents, my maternal grandmother, and her distant cousin, who moved to Luzon to seek refuge. Thereafter, the whole family system channeled its energy and time to survive the post-war era in the Philippines. Living in fear yielded a need for control and safety, a need that over generations turned into a legacy to control in the name of survival. This drove several of my relatives to move to other countries to seek greener pastures.

My parents, accustomed to blue-collar work (my mother, a nurse/factory worker, and my father, a warehouse employee) discouraged me from reading because it would hurt my eyes. Writing, and by extension, reading, or anything that resembles sedentary work, when there’s no “true” labor to witness, is deemed self-centered, lazy, and unnecessary. In my stories and essays, themes such as home, family, displacement, war, grief, and existential loneliness sprout like atomic mushrooms. In hindsight, I realized I’ve been writing about intergenerational trauma brought on by war.

Despite my family’s lack of fondness for reading, they are the best storytellers. They tell stories to pass time, to gossip, to warn, to scare us children, to reminisce how life used to be. Surrounded by strong-willed family members, I kept to myself and resorted to writing.

Writing is the only activity where I feel safe, free, and heard, where the page can hold space for me unconditionally amidst the chaos of history and modern times, where there’s no right or wrong, where I make my own rules, where I figure out how to live and survive like my ancestors. It’s a place of death and rebirth. When I leave the page, I’m a person with a new understanding of how to live. If not, then I get to imagine an experience or a possibility. Writing is an act of self-care, self-preservation, and a way to find my truth. And when someone reads my work and they understand where I’m coming from and what I’m trying to say, I feel a certain kind of kinship; a happiness and hope that I can’t find anywhere else.

Despite this, I’ve never confidently considered myself a writer. I create things to make sense of what it means to live and not just exist. Writing is just one of the many channels of self-expression and truth-seeking, a means to an end. It is an intellectual endeavor, and my mind is a moshpit. So before I write, I try to regulate my emotions and dispel anxieties because writing the first draft requires a sense of safety and play, a young child’s freedom.

Starting a piece is the most difficult part for me. The jumping-off point can be a sentence, a concept I’ve been toying with, a scene, a conversation I’ve heard. I go to the nearby coffee shop or any neutral place. Drink an iced cappuccino and start writing notes or chunks of texts that I can use. I freewrite really fast to discover where the piece can take me before anxieties creep in. I let everything pour out, resisting the impulse to edit myself prematurely. Usually, I write my first draft on my phone.

When I’m done, I rest and do something else. While doing that something else—working at my part-time job as an assistant, doing the chores, cooking, playing with my cats, looking for freelance work— I think. I think about the big picture. I think about the form—how should I present the story in a new way? How can I write my experience to arrive at a new understanding? I think about words, sentence structures, scenes. I usually start thinking seriously about the first sentence here. How should I write the first sentence to set the right tone or mood or introduce the themes as real and as honestly as possible? I look around me and absorb everything. I go outside for a walk and pay attention to my surroundings. I gravitate towards words and the feelings they evoke. I buy vegetables in the nearby market and eavesdrop on conversations between vendors and their patrons. How they structure their story or gossip. What words they choose. Why did she say nakikitira lang siya instead of nakatira siya sa lola niya? I look at shop signs and advertisements during my walks—This morning I saw a bright red pest control truck with the words D.I.A.L. in bold white letters: Daga, Ipis, Anay, Lamok! D-I-A-L Pest Control! Call now! I laughed hysterically as I walked back and thought about its rhetoric.

Then, when time and energy permit, I sit down in front of my computer and edit. This usually takes hours nonstop. I forget the world. I forget to eat. I forget to go to the bathroom. I forget myself in this flow state. Living alone makes this easier, but I would advise against this because it’s not healthy. Healthy habits get thrown out of the window during this period.

The Hemingway method works for me. I usually stop halfway through something before I call it a day so that when I repeat the process the following day, it won’t be such an uphill climb to write again.

But, in rare instances, a piece comes in full form, like a gift. There are times when I get jolted out of sleep at 4 AM, grab my phone and write the first draft continuously. Then I go back to sleep. Most times I forget that I’ve written something and it comes as a shock to me when I dig into my phone and read them.

Writing is 10% of the labor. The rest is about thinking and paying attention to life. My family has a knack for noticing things that many people would just brush off. Call it hypervigilance or a constant pursuit for safety, but I call it attention. I remember just driving around the city with my uncle and he told stories about walking in Avenida, Roxas Boulevard, and Chinatown in his youth and what these places meant and the people he met along the way. Listening to his stories, I notice how much attention he gives to life and the people in it. And I want to live and write just like that.

Wil-Lian L. Guzmanos was born and raised in Manila, Philippines. Her writing has appeared in Plural: Online Prose Journal and Tint Journal. She makes and self-publishes zines, namely Seed (2019), My Oh My! (2024), and Cats: A Photo Zine (2024). Her first book Kaleidoscope and Other Essays is forthcoming from Everything’s Fine.

JournalIXM by IXM Hakuhodo accepts and offers modest compensation for unsolicited short essays. We also publish short comic strips and reflections set to illustration. While we prefer pieces that deal with creativity and the creative industries, we remain generally open in terms of theme. Submit in pdf with a short bionote at shark.maitland-smith@hakuhodoph.com.